With virtually everyone sheltered in due to the ongoing pandemic, lots of us spend more time than we should perusing social media, becoming experts in all things coronavirus. I thought I would take the opportunity, as time permits while working from home (though perhaps I can count this as work, since I’m in the education business), to put together a few short (hopefully) informative lessons on what viruses are, how they work, how our bodies respond, how vaccines and antivirals work (and why it takes so long to get them made), etc.

DISCLAIMER: I don’t claim to be an expert on coronavirus by any means, but I do have a PhD in Cell and Molecular Biology, which I earned in the Molecular Microbiology and Immunology department at SLU many years ago, doing research in a virology lab, studying vaccine development and immune responses to viral infection. SO, I do have a little experience in this area, at least a bit more than the average non-science person, anyway.

So, my first “lesson” will be on the general characteristics of viruses. Viruses are described as non-cellular infectious agents, meaning that they have the capacity to cause infection, but since they are not cellular entities, they require a host cell in order to replicate (and really to carry out any functions). A nice science-y way to say this is that viruses are “obligate intracellular parasites.” The obligate part of that phrase means that it is a requirement…and the intracellular part of the phrase describes what the virus is obligated (or required) to have, and that is, a host cell for the non-cellular agent. Lastly, the term parasite is used. That is an apt description as viruses usually replicate and function at the expense of the host cell (and often host organism).

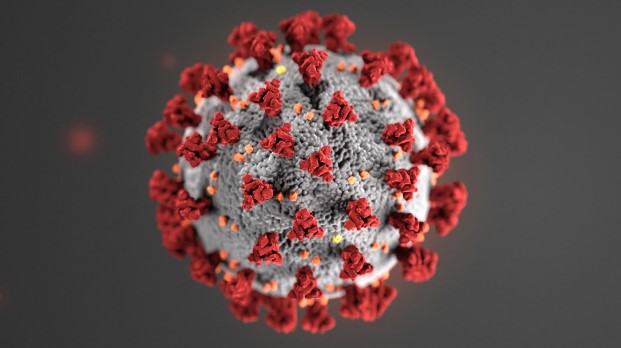

Viruses contain a genetic makeup of either DNA or RNA. And in fact, their genetic makeup is one of the broad categories often used to categorize or classify viruses. It is not uncommon to sort viruses into families of DNA viruses or RNA viruses. And then within the RNA viruses, there are additional variations on the theme, but I’ll save that discussion for a future lesson. This genome is usually encased within a protective coating called a capsid, and that capsid is often surrounded further by a lipid envelope, studded with protein “spikes”, that is acquired as it is assembled and leaves the host cell. See the accompanying photo below. This is the stock photo that many websites, including the CDC, are using to represent the current coronavirus. The gray represents the virus envelope, and the red things projecting outward represent the protein spikes. The entire virus as a whole, as you see depicted below, is called a virion.

In order for a virus to cause disease, since it cannot reproduce on its own, it must first be able to gain access to a host cell. This process is often aided by the protein spikes contained within the viral envelope. Those spikes bind to a protein on the membrane of the host cell, inducing a process called receptor-mediated endocytosis. That’s a fancy way of saying the binding of the virus to proteins on the cell membrane trigger the cell to import the virus. (There’s a really great visual of this process, but to avoid copyright infringement, instead of posting the photo directly into my blog here, I’ll provide this link that will take you directly to the figure.) This process is well-defined for a number of different viral infectious processes. For example, the proteins hemagglutinin and neuraminidase are two proteins of influenza that are found in the envelope and mediate the contact with and import into the host cell.

Once inside the host cell, the virus act sort of like a pirate and commandeers the intracellular machinery to copy its genetic material and produce its proteins. The virus itself is tiny and doesn’t carry along the equipment to accomplish this, thus the term “obligate intracellular parasite.” As new copies of the virus genome are made, and new virus proteins are manufactured, new virus particles can assemble and can be released from the host cell, either by budding through the membrane of the host cell, or by causing the host cell to rupture. Either way, this release of virus particles into the surrounding environment allows infection of neighboring cells, thereby propagating the infection within the host organism.

Since I want to keep these relatively short so as not to lose my readers, I’ll stop for now and pick up next time with more of the mechanics of a viral infection. Thanks for reading!

Nice job!!!

LikeLike

Uhm I need more!

LikeLike

Come back tomorrow! 🙂

LikeLike

This is so good, Lydia!

LikeLike